For skin microbiome explorer Julie Segre, her quest is more than skin deep

In the fourth century BCE, the Greek physician Hippocrates discovered that some people suffered from white, speckled, “cottage cheese”-like lesions in their mouths. Hippocrates explained the symptoms in his book Epidemics, which is thought to be the first known description of a fungal infection. The infection, commonly known as oral thrush, is caused by the fungus Candida albicans.

Ganguly: You are often called a genome detective. What kind of sleuthing are you and your research team doing these days?

Segre: We are using genomics as a high-powered microscope to determine what kinds of bacteria, fungi and viruses exist on human skin. And this includes the bottom of your feet, the bend of your elbow and your nose! We still have so much to learn about how all these different species interact on the skin and how they are affected or not affected by antibiotics. A big question we want to answer is how these microbes can be a boon and a bane depending on the circumstances, promoting human health and causing diseases.

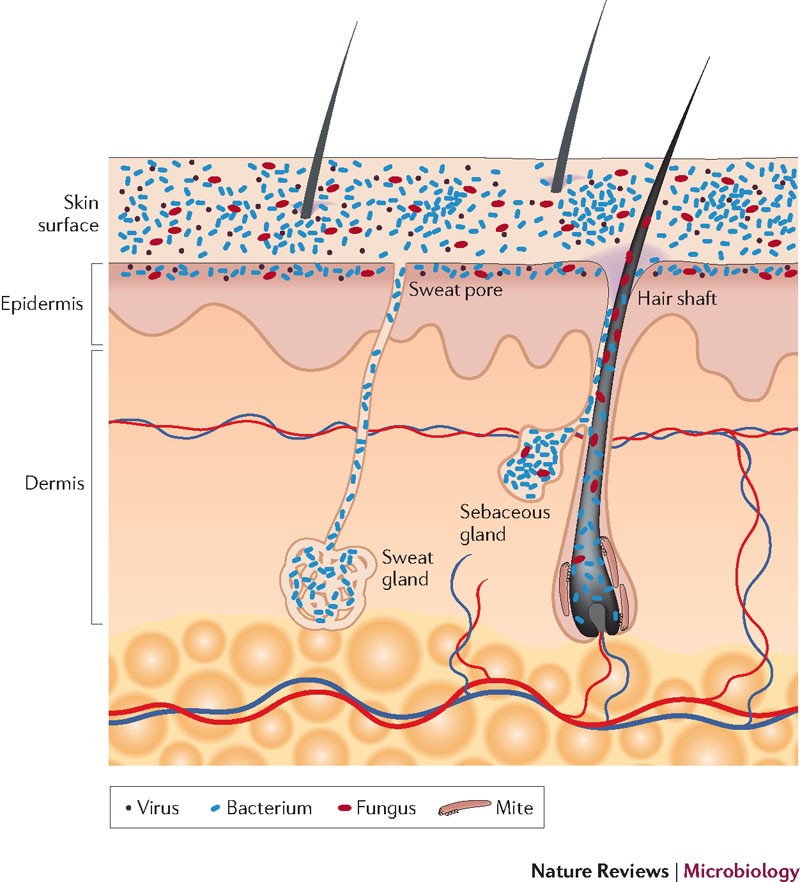

A view of the skin microbiome and the lower skin layers (Grice, E., Segre, J., 2011)

Ganguly: You and other researchers recently published a paper in Nature Microbiology showing that there are thousands of newly recognized microorganisms living on our skin. What was the biggest takeaway from that study?

Segre: Knowing which microbes live on our skin is hard! It's like piecing together a puzzle because the DNA of each microbe is cut into little pieces, then we need to put the whole genome sequence back together. Each microbe's DNA could be in 200 or 500 puzzle pieces, which should be simple to put together, but it's impossible to separate each microbe within a given skin sample. This means you have one giant box containing hundreds of small pieces, each from 200 different puzzles!

Ganguly: With such an accomplished career, do you have any special crowning moments you are particularly proud of?

Segre: Building a translational team for skin microbiome research with brilliant colleagues, using the best genomic technology and data sets. We’ve worked with clinicians from other NIH institutes and the NIH Clinical Center who see patients and used our genomic tools to find ways of treating them effectively. Translational research requires full integration from the clinic to basic research. Going back to 2008, I was one of the first scientists to stand up a microbiome-focused clinical protocol, and I am thrilled to see the project’s enduring success.

Ganguly: Do you have any recipes for success for budding scientists?

Segre: I’ve thought about our team as a three-legged stool, integrating genomics, microbiology and dermatology. What will you need to reveal the most scientifically accurate and meaningful answer? A genomicist? A dermatologist? A statistician? A microbiologist? Create a team that allows everyone to benefit from the group’s expertise while still questioning each other's preconceived notions to strengthen your research methods. You'll realize it's almost like a superpower.

Ganguly: Apart from your research, you are heavily involved in government campaigns and efforts. What made you join the Anti-Harassment Committee at NIH, and what can you tell us about changes that we can expect in the NIH community?

Segre: I got involved in the anti-harassment committee as an outgrowth of my work on the Women Science Advisory Committee. Through the committee, I could relate my issues as a woman scientist and listen to personal experiences of women, especially those from underrepresented groups. So many of the problems we are grappling with as a society tend to stay underneath the visible iceberg, and I wanted to play a part in building the groundwork to eradicate inappropriate, harmful behaviors from the community. We can't continue business as usual.

There is so much yet to be done, but we have rewritten the NIH Code of Conduct manual chapter where we explicitly state that gender harassment and other forms of harassment and bullying are unacceptable and will be addressed by the NIH CIVIL program, which at academic institutes would be akin to a Title IX office. This will make NIH more accountable and make us more consistent with other institutions and universities. Our workforce matters, and we need to create an impact for the next generation in a positive way so that the scientific culture flourishes.

Ganguly: You were also recently named the assistant director of health and life science at the Office of Science and Technology Policy. How do you feel about being appointed, and what does your role entail?

Segre: This is a crucial moment for science at the highest level of government and society. In that respect, it's an honor to work on scientific issues that will impact national policies. Initially, I worked exclusively on pandemic preparedness, and we published the plan in September 2021. It lays out the scientific and public health capabilities we need to prepare for the next pandemic threat. But beneath that is the need to address health [disparities] and provide deep-rooted support to our public health systems.

One of my main focuses is on the issue of containment of both pandemic threats and multi-drug-resistant organisms. How would we detect and then contain future pathogens before they spread, and what would that require? It’s all about figuring out this spot between what’s possible and what’s practical.

Ganguly: Any final insights on how you see the role of science in society?

Segre: This makes me go back in time. My father was a high-energy theoretical physicist. He worked with the Union of Concerned Scientists, a group that was deeply entrenched in the issues of nuclear non-proliferation and communicating their efforts to the public. The atom bomb, polio vaccine, HIV medication, the Human Genome Project and now COVID-19 — each event keeps highlighting just how vital science communication is.

I hope we can progress to a point where everyone has a clear and deeper understanding of how their genomic information, including their microbes, impacts their personal health. There is nothing more personal than your genome, and society needs to be alert and respond to how people understand or misunderstand what their genome is all about.

Last updated: January 27, 2022