Last updated: October 05, 2012

FDA approves crystal-dissolving eye drops, a major milestone for NIH rare disease researchers

FDA approves crystal-dissolving eye drops, a major milestone for NIH rare disease researchers

NHGRI, NICHD and NEI collaborated with Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals on new drug application

By Raymond MacDougall

Division of Intramural Research Associate Director of Communications

"This is an important advance for children and adults who suffer from cystinosis," said William A. Gahl, M.D., Ph.D., National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) clinical director, who spearheaded the research. "FDA approval of this drug represents the culmination of a longstanding collaboration among the National Eye Institute (NEI), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Human Genome Research Institute and Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals. It also has involved invaluable cooperation from cystinosis advocacy groups-the Cystinosis Research Network, the Cystinosis Foundation and the Cystinosis Research Foundation."

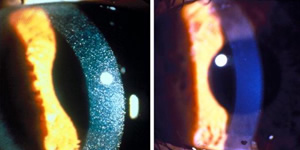

Cystinosis affects approximately 600 children and young adults in the United States and 2,000 individuals worldwide. It is a rare, genetic lysosomal storage disease, characterized by the abnormal accumulation of the amino acid, cystine. The disease causes cystine crystals to build up in various organs of the body, including the corneas, kidneys, liver, pancreas, muscles, brain and white blood cells. Corneal cystine accumulation can lead to eye complications such as squinting, foreign body sensations, changes in visual acuity, corneal haziness and sensitivity to light. Other complications of cystinosis include rickets, growth failure, muscle wasting, diabetes, hypothyroidism and difficulty swallowing.

Dr. Gahl's research team began studying cystinosis more than 25 years ago at NICHD, migrating the research to NHGRI in 2002. Though rare, the condition presented a heartbreaking challenge. Without treatment, children with cystinosis undergo kidney failure and die before age 10. A kidney transplant can prolong life, but the disease continues to damage other organs, including the eyes, muscles, pancreas and brain.

In 1982, Dr. Gahl and others determined that the basic defect in this lysosomal storage disorder is the impaired transport of the amino acid cystine out of lysosomes and into the cytoplasm of cells. In addition to fighting infection, lysosomes break down unneeded proteins so the residual amino acids can be salvaged for future use. In cystinosis, the transporter protein that carries one of these salvaged amino acids, called cystine, out of the lysosome and into the cell cytoplasm, is either defective or missing. This causes cystine to build up in the lysosome and form crystals, which ends up destroying both the lysosome and the cell around it.

Dr. Gahl's team was instrumental in establishing a drug called cysteamine as the treatment of choice for cystinosis. Cysteamine breaks down cystine and keeps it from building up in the tissues, thereby delaying or averting kidney failure, improving the growth of children with cystinosis and preventing late complications of the disease. Since joining NIH in 1981, Dr. Gahl and his colleagues have seen more than 300 people with cystinosis, and some of his patients who are taking cysteamine are now 40 to 50 years old.

However, cysteamine in pill form cannot reach the cornea to prevent irritating and vision-threatening symptoms. An eye-drop solution met the unique need for treating eyes and an NEI study commenced in 1986. In 1995, Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals, Inc. began manufacturing the eye-drop solution, trademarked Cystaran™, under an orphan drug provision from the FDA. Pharmaceutical products developed specifically for a rare condition may receive this designation. This drug now is the only FDA-approved, ophthalmic treatment for cystinosis.

The clinical safety and efficacy of the ophthalmic therapy were previously evaluated in controlled clinical trials conducted by NIH in approximately 250 patients. Results of these studies support the use of ophthalmic cysteamine as an effective treatment for corneal cystine crystals. "Cysteamine treatment has dramatically changed the course of this disease," said Dr. Gahl. "The approval of oral and topical [eyedrop] formulations of the drug is a homerun for cystinosis patients."

For the past 26 years, cystinosis patients enrolled in an NEI clinical study have travelled to the NIH Clinical Center about once a year, where doctors have administered the eye drops and recorded successful results. "We know the drops work, and that lots of people benefit significantly from using them," said Rachel Bishop, M.D., M.P.H., chief of NEI's Consult Service Section and current principal investigator for the treatment trial. "This is a major development, because there are no other approved ophthalmic treatments for cystinosis. For the first time, patients all over the country will now have access to treatment."

In a news release issued after the FDA approval, Sigma-Tau Chief Operating Officer David Lemus said, "This new medicine will offer physicians the only FDA-approved treatment for patients with corneal cystine crystal accumulation, many of whom are children and whose lives are seriously impacted by this debilitating chronic condition."

For a picture of one patient's corneas, before and after treatment, go to www.genome.gov/dmd/img.cfm?node=Photos/Technology/Medical%20Conditions&id=79209

Posted: October 5, 2012