How do you toast a gene therapy trial? With tea.

It’s teatime and doctors, researchers and patients are at the table. They celebrate a decade of work and launch the first in-human gene therapy trial for children with a rare and devastating disease, GM1 gangliosidosis.

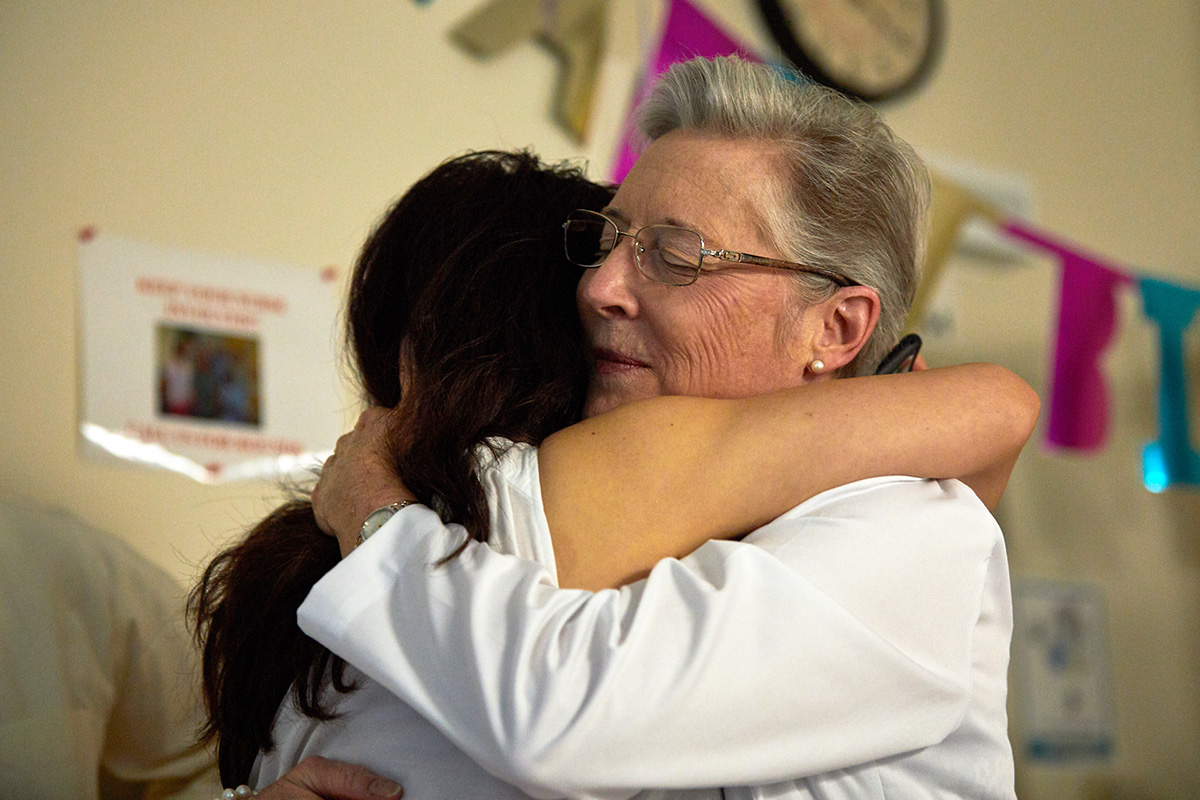

Cyndi Tifft opened a bag and pulled out one of the items inside: a teacup. It was painted with colorful flowers, and gold trim adorned the rim. Written across the bag, in an 8-year-old’s scrawl, was "For Dr. Grandma. Thank you. Love, Jojo."

Tifft was getting ready for Jojo's tea party of a lifetime. What would happen after, while young Jojo napped, would be the culmination of a decade of work and a new life for someone with a devastating disease. Jojo was about to receive the first experimental gene therapy treatment for the rare disease, GM1 gangliosidosis.

A faulty gene halts a critical process

Dr. Tifft, a geneticist at the National Human Genome Research Institute, first met Jojo in 2016. Jojo and her mother, Lei, arrived at the NIH Clinical Center with their tea set when they volunteered to take part in Tifft's natural history study. For 10 years, Tifft followed 35 children with GM1 gangliosidosis to see how the disease developed, hoping to gain insight into treatment options.

During her first visit, Jojo renamed all her doctors. She dubbed her six-and-a-half foot tall neurologist, "Dr. Big Shoes." By the end of the week, she called Tifft, "Dr. Grandma." When Tifft hears that name she beams.

When Tifft met Jojo, she was walking, talking and writing. Now, three years later, Jojo needs help standing, speaking and just about everything else. She has a disease that attacks nerve cells in the brain, rendering them useless, one by one.

When Jojo was born, GM1 gangliosidosis was already wreaking havoc on her neurons. At the time, no one knew.

Jojo inherited the genes for GM1 gangliosidosis from her mother and father. Though both parents are healthy, they each have a mutated GLB1 gene. With only one mutated copy, they are considered carriers, and are unaffected. GM1 gangliosidosis manifests in people with two copies of the mutated gene. Jojo inherited one from each parent. This inheritance pattern is called autosomal recessive. The odds of two carriers meeting and passing on their mutated GLB1 gene are slim; on average, only about one in 100,000 people has GM1 gangliosidosis.

Molecules, called gangliosides, align neurons and act as signals. They tell our body how to do things like talk, walk or chew. As they age, gangliosides are broken down in the lysosome, the recycling center of a cell. After old ones are dismantled, new gangliosides are built.

Within the lysosome is a team of enzymes, which are like workers in the recycling plant. Each has a specialized role. Together, they break down complex molecules, like gangliosides, that the cell no longer needs.

Imagine the workers in an assembly line. Their job is to take apart a ganglioside made of sugars and fats. The first worker cuts off the first sugar, the next worker cuts off the next sugar, and so on. The process is smooth and methodical. But people with GM1 gangliosidosis aren't producing the first worker - the enzyme that starts the process. Without that enzyme, the recycling effort is halted before it even begins. A backlog of gangliosides creates a blockage that overwhelms the system. New signaling molecules aren't built, neurons stop functioning, and processes like walking, talking and even breathing slow down and eventually stop.

How to deliver a new gene

Tifft had set the tea tray in front of Jojo. Under her lab coat she wore a long blue gown. But nothing compares to the striking red and gold gown and tiara Jojo wore. Her mom, Lei, wore a matching red skirt.

“Red signifies energy,” Lei said. It was an energy everyone felt reverberate through the room.

"Cake for breakfast is the best," Tifft said. Her voice carried over the chatter of more than 30 people packed into the tiny hospital room. Jojo sat on the edge of the bed supported by a caregiver as Tifft offered her a bite of mango cake. She washes it down with orange juice from a teacup. The tea party has been a tradition for the pair since Jojo started seeing Tifft. Only this tea party was different. On this day, Jojo would receive the first in-human gene therapy that could be an effective treatment for GM1 gangliosidosis. The people surrounding her spent the past decade in a massive effort leading up to this day.

In the 1970s, medical and veterinary researchers joined forces when they found a cat that had GM1 gangliosidosis. The veterinary researchers said the disease was as relentless in cats as it is in humans. The cats with GM1 gangliosidosis lost their ability to walk or even stand.

The two researchers from Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine, Douglas Martin, Ph.D., and Heather Gray-Edwards, D.V.M., Ph.D. (now at University of Massachusetts) said that after meeting Tifft they attempted a matching natural history study in cats. They found that cats responded to the disease in the same ways humans did. The disease progression in their cat study paralleled the progression in the humans of Tifft’s study. Cats made the ideal animal model for the first gene therapy test.

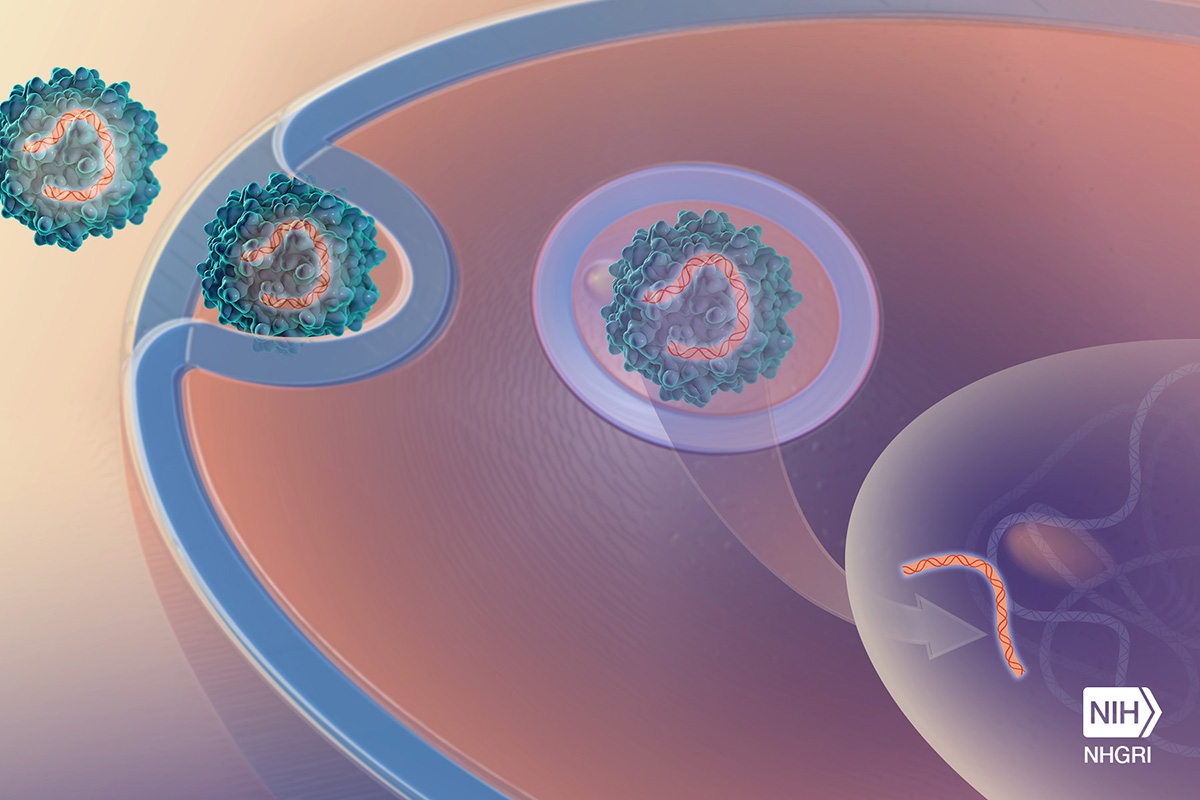

Miguel Sena-Esteves, Ph.D., associate professor of neurology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, was instrumental in creating the gene therapy vector -- an unwitting virus that would deliver functioning copies of the defective GLB1 gene to the cat's brain cells.

Viruses are ambitious. They try to take over their micro-world by delivering their genes to the host and replicating themselves. Viral infections are generally viewed negatively. Take the flu virus, for example: It moves into the respiratory tract, binds to the surface of cells, and inserts genetic information, causing fever and aches.

Because of their drive to rampantly conquer and sow their seed, could viruses be harnessed to do the same work, except deliver helpful genes? Sena-Esteves attempted exactly that by removing the guts of a harmless virus and replacing them with a healthy gene that is programmed to make the missing enzyme. The new gene will use the cell's machinery to make the much-needed enzyme. But they only get one chance to get it right. Once the virus enters Jojo's body and delivers the gene, she will start making antibodies to fight it. That rules out the option for a “redo,” because her body will have built a defense army to neutralize the virus vector.

The gene therapy vector was successful in safely treating the cats with GM1 gangliosidosis. With the new gene, the lysosome factory worked without a glitch and neurodegeneration was no longer a concern. This demonstrated to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that they were ready to test the treatment on humans in a clinical trial. Now, Edwards, Martin, Sena-Esteves, and everyone else in the room, were on the edge of their seats anticipating the trial.

"Let's hope we didn't spend the last 10 years doing something that will only work in animals," Sena-Esteves said lightheartedly, then adds, "How many times have we cured cancer in mice? Thousands."

But Sena-Esteves said his confidence level is high. "The only regret that I have is it took so long to get here," he said, adding that had their work moved along sooner, then maybe they could have helped Jojo before the disease progressed as far as it did. Still, Sena-Esteves recognizes how this trial will impact future children with GM1 gangliosidosis. "What this child did is open the path for everyone," he said.

Bits of mango tea cake covered Jojo's face as one-by-one she playfully gave everyone a “mango hug,” sprinkling crumbs on their cheeks.

"Thanks a lot, Cyndi," Martin said to Tifft, the instigator and only one who escaped the mango hugs. Tifft laughed. No one worried about the sugary crumbs because, to them, this day represents more than a decade of work, cross-continental collaboration, and new hope for those suffering from this devastating disease.

"This day is right up there with my wedding day and the birth of my kids," Tifft said.

Waking up to a second chance

With the lights out, the crowd quietly gathered in the hallway. Jojo was falling fast asleep in the hospital bed.

It was time.

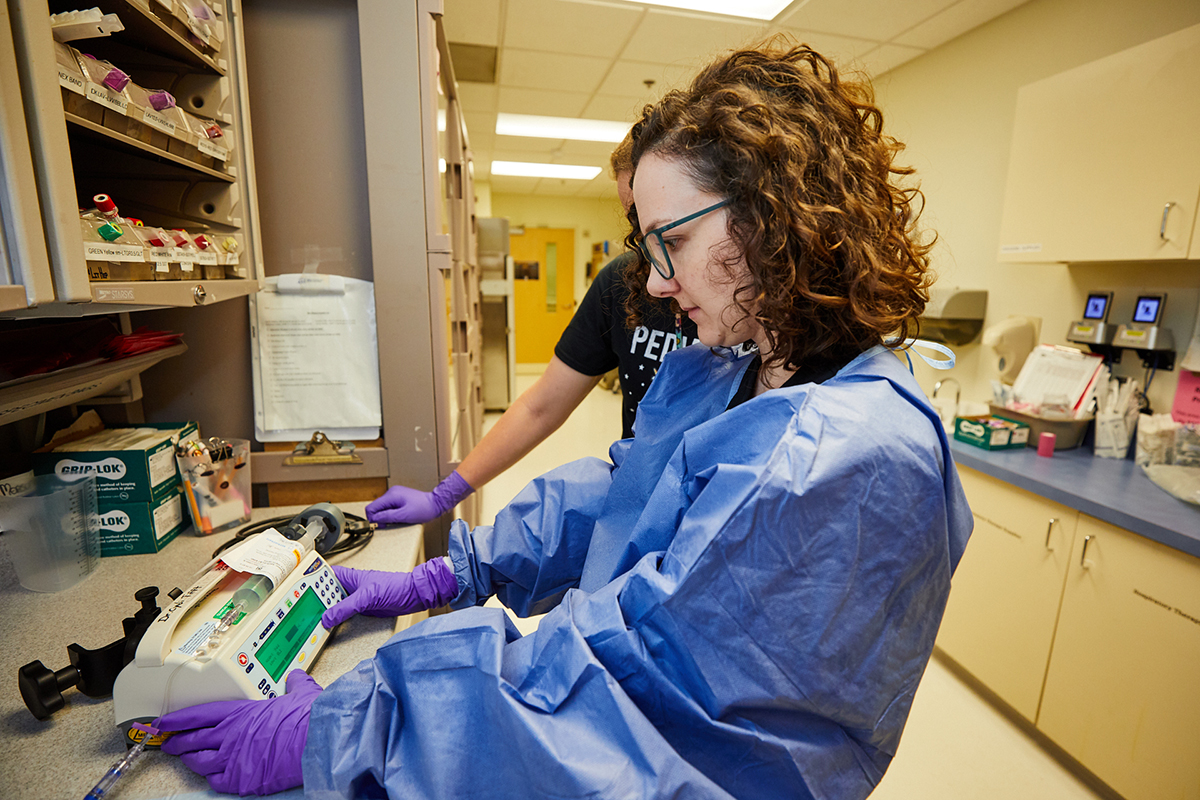

Two nurses measured and prepped the perfect amount of the gene therapy vector. They double-checked the protocol and measurements twice over. Jojo was napping in her hospital bed, still wearing the party dress and clutching a stuffed animal.

The nurses moved past the crowd and entered the dark room. Everyone looked at each other, whispering, "I think we should wait out here," and "There isn't anything to see anyway. She is just napping." But no one could help themselves, and one-by-one, all 30 people tiptoed into the room.

Everyone watched Jojo as she received the gene therapy vector, delivered through an IV drip while she slept. People snapped pictures, celebrated, laughed, cried and embraced one another. The party continued, quietly.

When Jojo awoke, she was the same girl with the same neurological challenges. Tifft will monitor Jojo for the next five years, looking for changes in her cognitive abilities. Tifft said, "theoretically humans are born with all the neurons we will ever have. We aren't regenerating new ones.” At the very least, she expects that Jojo's condition will stabilize. This outcome would be a huge success and enough to move from the clinical trial phase to a new drug approval in two years. However, there was also a feeling of optimism in the room. Many anticipated that the treatment could reverse some of Jojo's decline, helping her regain the ability to walk or talk.

"She is still developing. The cats finish developing at eight weeks, but Jojo's brain continues to develop until she is 18 years old. I'm hopeful that we can reverse a lot of this stuff," Gray-Edwards said.

Tifft has plans to launch a broader clinical trial this fall. Her team will select eight children to undergo the same treatment and monitoring protocol as Jojo. Then, if all goes as planned, the team will have an effective treatment for GM1 gangliosidosis. Children could have their genes tested in the womb or at birth. With one dose of the gene therapy, they could avoid a lifetime of decline.

"I keep pinching myself," Lei said. "I've dreamed about this hundreds of times. Then I wake up and reality is not great. I think Jojo deserves a chance." Lei has been a driving force for ensuring this clinical trial would happen for Jojo and the next children. She knows precisely what is at stake. That morning she asked her daughter, "Jojo, do you know why we are here?"

Despite the short inarticulate sounds Jojo makes in response, Lei understood her reply.

"Hope," Jojo said.

Last updated: July 23, 2019