Last updated: November 29, 2012

Do genes make us keep our fat jeans?

Genome Advance of the Month

Do genes make us keep our fat jeans?

By Andrea Ramirez, M.D., M.S.

Clinical Fellow, NHGRI

|

But why can't we keep the weight off? Do genes make us keep our fat jeans?

In the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Viviana F. Bumaschny, M.D., Ph.D., from the University of Buenos Aires and her collaborators there and at the University of Michigan sought to answer this question. To do this, they changed a gene in mice and watched how much they ate and tracked their weight. This gene, called proopiomelanocortin or POMC, makes proteins in the brain that reduce appetite, which leads to normal food intake and weight. Previous research has shown malfunction of this gene causes increased appetite, weight gain and obesity.

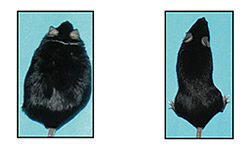

Dr. Bumaschny and colleagues created a mouse with a special genetic switch to control POMC. This switch allowed the researchers to turn off the POMC gene when the mice were born, which caused overeating and obesity, and then turn it back on at different times, allowing the animals to return to a normal level of appetite and eating.

They found that if the POMC switch was turned back on early in life, the mice were able to return to a normal body weight and avoid obesity. But in mice in which the POMC switch stayed off longer, the mice remained overweight and started to creep back towards their previous high. This was true even though the mice ate less and initially lost some weight. In other words, the longer the mice were obese, the harder it was to return to a normal weight. The news wasn't all bad. Though these mice remained overweight, the negative health effects of obesity, including fat in the liver and diabetes, were reduced.

More than two-thirds of U.S. adults are overweight or obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, so we're all too familiar with a similar pattern of obesity in humans. We may have success losing weight in the short term, but then creep back into those bigger clothes over time, as if the heavier weight had become a new set point. Fortunately, like the mice in this study, people who achieve even modest weight loss also improve their health.

This work suggests that genes, including POMC, may be to blame for why losing weight and keeping it off is so hard. It also emphasizes why we should be very careful not to gain it in the first place — a little extra motivation to avoid second helpings as we approach the season of feasting.

Read the article:

- Obesity-programmed mice are rescued by early genetic intervention

Viviana F. Bumaschny, Miho Yamashita3, Rodrigo Casas-Cordero, Verónica Otero-Corchón, Flávio S.J. de Souza, Marcelo Rubinstein and Malcolm J. Low. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 122(11):4203-4212. 2012.

Posted: November 29, 2012