Transformative Research

Rohith is just one of many examples why the transformative research taking place at NIH is critical. The same cutting-edge clinical medicine that was used to help Rohith might help other patients.

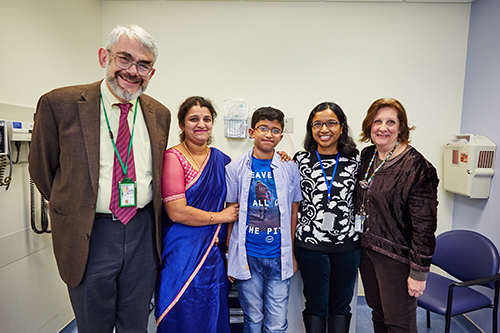

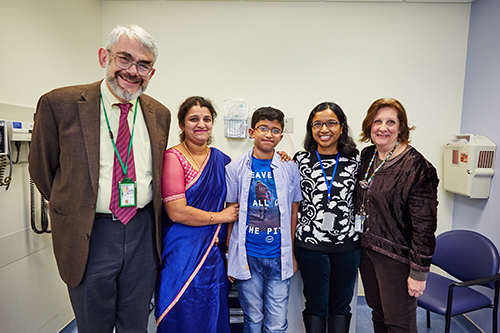

"My life has improved to a vast extent," said Rohith, in an interview in April 2018. "Dance is my favorite thing to do. After coming to NIH, I can run, dance and do all my favorite activities. My experience here has allowed me to be fit and happy in my life back home."

Rohith's story, like many others, can be described as no less than a diagnostic odyssey. Numerous doctors and tests later, there was still no explanation for his symptoms, explained Dan Kastner, M.D., Ph.D., scientific director of the National Human Genome Research Institute's (NHGRI) Division of Intramural Research and head of the Inflammatory Disease Section at NHGRI.

Dr. Kastner, who specializes in inflammatory conditions, was contacted by Rohith's doctor in Bangalore about a year and a half ago, when the physician was stumped by the symptoms Rohith was displaying. Rohith had been diagnosed with arthritis and a condition known as chronic, recurrent, multi-focal osteomyelitis (CRMO), or inflammation of the bone.

"Children who have CRMO can have inflammation in one bone, and then in a different bone," said Dr. Kastner. "Sometimes it can be multiple bones at the same time. It's extremely painful. Rohith also had recurrent high fevers and swelling of the salivary glands."

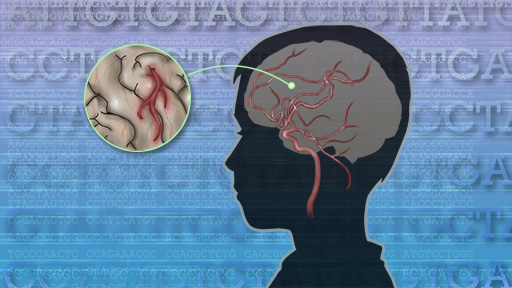

From previous tests, the doctors knew that the cause wasn't due to an infection. It must be genetic. Dr. Kastner requested blood samples from Rohith and his sister and parents to be sent from India to his lab at NHGRI. Dr. Kastner's team wanted to use genome sequencing to try to pinpoint if Rohith's condition was caused by a genomic mutation and, if so, where in his genome it lay.

The research group sequenced the parts of the genome that code for proteins, known as the exome. They found that Rohith had a mutation in both copies of a gene involved in a process that affects protein function known as ubiquitination (a modification of a protein after it has been translated). In this case, the effect leads to a form of cell death that causes inflammation. Dr. Kastner had a hunch from the scientific literature that the mutation might be causing Rohith's bone inflammation.

In March of 2017, Dr. Kastner was invited to give a scientific presentation in Bangalore. Coincidentally, his hotel was across the street from the hospital where Rohith was being treated so he set up a meeting to see him.

"Rohith had lots of pain in his foot and he was limping," Dr. Kastner said. "In my lab, our mission is to use what we find in a person's genome to find a treatment. Could our team help?"

Dr. Kastner and his team started the process to get Rohith and his family visas to the United States for a visit to the NIH Clinical Center. Having Rohith here at the NIH Clinical Center would help them understand as much as they could about his mutation and apply the treatment under the watchful eye of the NIH Clinical Center staff.

"The genes that turned up in the genomic analyses of the disease we focus on belong to inflammatory pathways, like Rohith's, that have been targeted by big pharmaceutical companies," said Dr. Kastner.

The team thought that one solution might be a common drug known as a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, prescribed worldwide to treat inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease. In July 2017, Rohith and his family got their visas approved to visit Dr. Kastner and his team at the NIH for two weeks, with a follow-up visit a month later. The doctors did blood work, x-rays and bone scans and put him on a TNF inhibitor to see if it could be used for to treat his condition.

"We had set-up a wheelchair to greet him when he returned, but he didn't need it!" said Dr. Kastner. "His lab tests have showed that his inflammation had normalized from the medication we had put him on."

"I came to this new and exciting world of the NIH Clinical Center and I believed that the doctors would cure me," Rohith said. "I am so thankful and grateful to them."

"While not every patient will go from wheelchairs to winning dance contests, this experience was a life-changer for Rohith and his family," said Kalpana Manthiram, M.D., a clinical fellow with Dr. Kastner's research team. "This story highlights what the NIH Clinical Center can do that's hard to do somewhere else. From using mechanistic studies and genome sequencing to inform your patient care - that's unique to NIH."